By Rev. Fr. Attah Anthony Agbali

Anyigba Night-time Masquerade, Security and Popular Imagination

I grew up in Anyigba in the 1970s well into the early 1980s. During this time, there was the Egwu Abdu that predominated the consciousness of most Anyigba’s residents and visitors. Egwu Abdu was a nocturnal masquerade. This was a very highly feared and revered masquerade that knew no person, no matter your social standing so it was alleged.

In Igala society, generally men can normally visualize, be in the presence, and interact with masquerades. Men are bound never to reveal any secret they know about any masquerades. Masquerades are alleged to possess extraordinary ancestral powers—even of life and death, and thus are both paradoxically valued and feared by all.

In a sense, masquerades are both sources of hot and cool; dangers and blessings. However, ideally according to Igala cultural traditions and social customs, the norm is females-old and young, and including to an extent children though better them than females, are ideally not allowed to visualize or encounter a masquerade. This, according to Igala customary traditions, is an enormous abomination.

In most cases violation requires the performance of certain cleansing and purification ritual actions to effect the erasure and elimination of the ascribed dangers portended by any such occurrence. Further, this is considered even more dangerous especially for pregnant women. It is alleged that their in-vitro pre-term babies would be born looking like such masquerades, hence born ugly. But in the case of the nocturnal masquerades, including Egwu Abdu, even men are under normal situations not exempt. It was a dangerous masquerade to meet or behold. I do not know how many men then living in Anyigba have ever met, or knows how the Egwu Abdu looks.

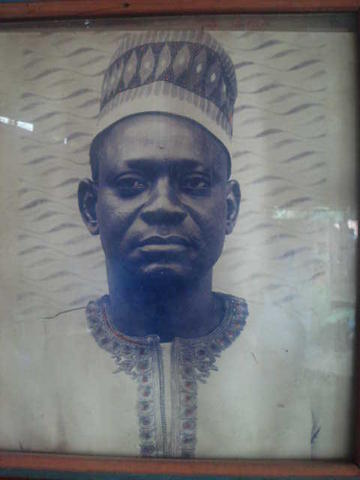

The Egwu Abdu, according to many of my mainly elder male sources, I heard from during the period, was brought to Anyigba from Oron, Akwa-Ibom State, in the Nigerian South-South region, by one Alhaji Abdul Adehi. Hence, the name Egwu Abdu (Abdu is the Igalanized form of Abdul) for which the masquerade was popularly known.

This fact is interesting for two predominating reasons. First, it now historically known, especially through the work of the late Igala anthropologist and cultural expert, Chief (Dr.) Tom [Thomas Miachi that some Igala masquerades derived their aborigine and material cultural forms from outside Igala territories. He locates the origin of such cultural diffusion from such extrinsic alien sources extrinsic to Igalaland from such cultural/sociolinguistic groups such as the Nupe, Jukun, Idoma, Ebira, Hausa (Akwuchi/Akechi), and limitedly from Edo and Igbo sources within the Igala cultural vicinity and region.

The Egwu Abdu reflects the first known case of cultural borrowing and extensive adoption of a masquerade from that far afield outside of the vicinity of the immediate Igala cultural area to the south. This is novel, though Igala precolonial historical and commercial activities and interactions with cultural and ethnic groups in this area is well known and equally documented. Igala through control of the trans-Atlantic slavery (triangular trade) and legitimate trade had also an extensive relationships and influences in the South-South region. Regionally, precolonial trade routes from the Middle Belt area, especially the ancient Kwararafa confederacy cut across the area, connecting the Igala and Aro trade routes, and extending through the Cross-Rivers trading zones into the Atlantic.

In modern times, with the colonial advent and missionary activities, the Qua Iboe (an adaptation of the Kwa Iboe river from which Akwa-Ibom also derives) Church (now the United Evangelical Church and its split entity) that predominates in certain parts of the Igala cultural area derived from the Akwa-Ibom cultural area. Efik and Ibibio teachers and missionaries also provided instructions and were arrowheads of evangelization in this Igala area, somewhat imprinting both their dual heritages both as Christians and geo-cultural formations. It is also instructive that the very first Roman Catholic bishop of Idah diocese, the late Bishop Ephraim Silas Obot, equally originated from the same Akwa-Ibom cultural zone.

It remains conjectural to determine whether, the above factors played any considerable or vague role in what could have possibly driven and informed the adaptation of this masquerade form, from Oron into the Igala cultural area.

A possible explanatory guess, with high probability, could imagine that shared stories, especially diffused through the educational systems maintained by the Akwa-Ibom aborigine missionary agents, could have propelled interests regarding this unique masquerade form. Imageries painted about such cultural phenomena could have stoked certain popular fascination with this masquerade’s unique form. Such filtered dissemination, could possibly without any conclusive determination, be at the root of the imagination that drove Alhaji Adehi to adopt and introduce the Egwu Abdu into Igala society at the time. Yet, the real reasons behind this decision would remain masked; buried with Alhaji Adehi upon his death.

This masquerade operates at late nights almost daily. The masquerade is assumed to walk alone around the Anyigba vicinity and adjourning suburbs—Oganaji, Ajetachi, Ofudu, Oforo, Ona-Iyale (Iyale Road), Ona-Egume (Old Egume Road toward Ankpa), and even Agala-Ate and probably Agala-Ogane too. The Egwu-Abdu, as a nocturnal masquerade, once outed at night strikes fear into the hearts of residents and visitors into Ayangba town who kept late nights.

The masquerade is supposed to have the powers of bilocation or multiple presence at different spaces at the same time in the night. The masquerade was a one person super-security outfit, all by and in itself. Its purpose was to provide security coverage for the entire Anyigba region, including her suburbs all throughout the night hours, though in certain areas of Anyigba the local vigilantes (Alode) monitored any night traffics at set points with road-block checking posts at all entry and departure points of Anyigba town.

People feared the Egwu Abdu.

The Egwu-Abdu was alleged to have the power of multi-location. The Egwu Abdu was equally supposed to have a ghoulish and deep booming voice that reverberated everywhere throughout the entire Anyigba area. It was even assumed that when the Egwu Abdu speaks you could feel the masquerade was right in the front of your residence. This reverberating voice also added to the mystique of the Egwu Abdu. The fear of Egwu Abdu predominated consciousness. At times felt In the evenings, many folks are running to be in their houses trying to avoid any kind of encounter with this dreaded nocturnal masquerade. Visitors shivered should they enter Anyigba late at night. The fear of the Egwu Abdu, was palpable and paralyzing.

Another vital aspect of the Egwu Abdu phenomenon of interest relates to its defining identity, harboring the name of its owner as a personalized entity—as Abdu’s masquerade. Typically, Igala masquerades all ideally belong to the Attah, and are under the overall control of the royal masquerades’ hegemon, Ekwe in Idah. Though true that individuals, especially at local and rural settings birth masquerades into being, such close association with their personal selves or names, is not very usual. Igala masquerades such, as Ukpokwu, Adaka, and others are normally not known to be so personalized or privatized, as they belong to the entire community, even if they are “birthed” by a human progeny.

I believe that Amuda one major exception. Maybe, this is because Amuda is not a performance masquerade but rather a ritual and witch-hunting and sorcery-weeding masquerade. Igala masquerades even if owned or procreated by individuals are communal rather than personized. I believe there’s a certain sense too that Egwu-Abdu, in performing a social function that limited night outing and activities, scaring off thieves and evil persons, does also possess collective and communitarian qualities.

Therefore, in every sense, the Egwu Abdu was a kind of unique masquerade form, and we can alternately assert it also as an aberration outside of the Igala conventional masquerade form. But above, all the Egwu Abdu was unlike most Igala masquerades not a performance masquerade as such. It was usually not seen during the day, and most persons do not know its material forms. In fact, there were some who believed that the Egwu Abdu was a total spirit, without material form. While, such views are debatable, the striking thing is that Egwu Abdu disappeared from the social and cultural psyche of Anyigba society in the first part of the mid-1980s.

Alhaji Adehi was a well-known Anyigba personality. He was a very wealthy man, landed property and real estate owner, engaged in farming with ownership of some tractors. He also had some swath of orchards and other economic trees in different parts of Anyigba, especially around Oganaji. He seems to spend his time around his upstairs building in downtown, Anyigba within the vicinity of the present garage (the old market)—which also housed motorized farming equipment (tractors, etc.) and other businesses, and Oganaji.

I knew Alhaji Adehi awesomely well. He was a towering Anyigba personality with elegant features, and dexterously swift. He was an Anyigba community leader by all reckoning, with the likes of Alhaji Musa Idakwo (the tanker owner), Alhaji Onegula, David Acheneje, Musa (Michael) Uduh, Udama Bookshop, Matthew Edogbanya, Mr. Patrick Achor, Yakubu Agbanagba, Alhaji Sule Akagwu (Sule Ogbuefi), Colonel Hassan (the late Eje of Ankpa), Mr. Attah Odoma, Mr. Adejoh Ataja, Mr. Francis Agi, Peter Opitical (Optical); Mr. Franklin (Mechanic), Hajiya Ina, among so many several others that I cannot now fully name, that dominated the social and economic firmament of the 1970s and 1980s Anyigba.

Alhaji Adehi was my dad’s friend—well growing up is like Dad knew everyone and everyone knew Dad in Anyigba. I also knew him on another level through my mischievousness. His orchard with cashews, mangoes, guavas, and different fruits were located on the way to or from school, around our Local Government Primary School, Oganaji, Ayangba. Stories of how not to mess with Alhaji’s fruit trees were well know. Even my dad and mom reiterated it and sternly warned us not to even try.

Of, course, good parental advisory. Even more, a few times that Alhaji visited our house, I overheard his conversations talking of how he deals with those ‘rascally” Oganaji school boys that wouldn’t leave his fruits alone. Boy, was it scary? I bet it was. Thus, I kept off bound, in spite of the allure until this one tempting day, when urged by a classmate to pluck off some plumb and juicy looking cashew fruits and lusciously tempting mango trees. I had initially resisted until he called me a coward.

Brow beaten I hastily climbed up and plucked some really good juicy cashews, then velvety mangoes down to those on the ground. Yes, all too suddenly, still throwing fruits down I was oblivious that the other school kids had ran off. Alhaji, who was hiding had emerged. Unlucky for me, my school bag was left on the ground. Alhaji grabbed all our school bags he could find, and we knew now there wasn’t an escape. I had become one of those naughty Oganaji school boys Alhaji used to boast about of dealing with to my dad.

Alhaji, lifting up his eyes spotted me right up there on the mango tree and entreated me to gently climb down. With my bag in his firm possession, there was no escape, even if I may. I started pleading for leniency, saying I was a first offender. I had to, my bag and my books were all in his possession. I couldn’t do much. He asked me of my name, then sorted through my bag to know if I was lying. Knowing my day, he uttered his utmost dismay—my dad as Vice Principal, at the CMML Secondary School, Anyigba, had a reputation and knack for discipline. Of course, further pleading was needed to spare my being reported to my parents, which of course meant “double whammy” trouble. “Double wahala for deadi bodi,” apologies to the Abami Eda, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti.

Yes, I do know Alhaji Adehi! From that day on dreading Alhaji Adehi, there was no tempering with his economic trees, in the same way Anyigba folks dreaded any sort of encounter—wittingly or unwittingly—with his masquerade!

Anyigba society had begun to vigorously open up to modernity. Hitherto, Ayangba was a transportation hub, connecting travelers, though still steeped in traditions even if a more open society. In the days of Kwara State, with the state’s headquarter far from Anyigba in Ilorin, many persons had to travel through Anyigba, onward Dekina, then to Shintaku, which was a ferry depot transporting travelers across the confluences of the Benue and Niger rivers into or from Lokoja, on their way to Ilorin.

The administrative businesses, especially those of state employees conducted in Ilorin, engendered much traffic flow this wise. Hence, Anyigba was a road network nexus. Thus, persons traveling to Ilorin from Idah or Ankpa (the rest of Igalaland) must by necessity pass through Anyigba. This brought economic prosperity and the traffic flow through it fastened its material and social development. Anyigba acquired a new identity and consciousness both as an economic site and a transportation hub.

The Anyigba motor park (garage) became something of a specter and a melting pot of the Igala universe. Anyigba motor-park (garage) bustled and glittered. Hence, the music “Igareji Anyigba e” an enriching old music burnished into modern consciousness by the Igala musician, T.J. Bala bespeaks of the Anyigba of this era. Anyigba also became a sort of cultural entrepot, where travelers preferred to anchor their journeys on their way from Shintanku, or into Anyigba from either Ankpa or Idah. This cultural dynamics enriched Anyigba’s economic, cultural and social life.

By 1976, though the Igala part of Kwara State had become conjoined to the Tiv and Idoma of the old Benue-Plateau into Benue State, Anyigba still maintained its dominance, as it still was on the route to Makurdi from Dekina and the Idah area. However, with expansive cultural changes motivated hugely with the establishment of the World Bank funded, Anyigba Agricultural Development Project (AADP) about 1978, certain traditional features of Ayangba cultural life had begun to give way.

The passage into modernity enormously affected Egwu Abdu’s ability to hold sway. Its base cracked, the imagination that made Egwu Abdu once scary now eclipsed and overshadowed, Egwu Abdu disappeared, gone with its spirit. Egwu Abdu, as a spirit being couldn’t stand to be brushed by materiality and scratched and unveiled. Egwu Abdu took the part of honor, refusing to suffer undue humiliation and insolence. Once the social foundations crackled that upheld Egwu Abdu’s relevance, it realized without hesitation that its time was up. Egwu Abdu quit and made a noble exit; including from the consciousness of the society where it once held dominance and strode and danced its spirit cat-walk.

The social forces that underlay the existential relevance of Egwu Abdu undermined and assaulted by modernity forcefully crumbled enormously. The AADP and her heavy duty machines were rampaging and humming noises that drained the hitherto reverberating and chilling voice of Egwu Abdu. If Egwu Abdu could not hold sway it refused to play ball. As the caterpillars rolled into the Anyigba forests disrupting the peace of spirit forces, Egwu Abdu knew it wouldn’t take long. Her game was up. Through crackling and crumbling sounds, Anyigba was changing for good, its own modern good, and also harbingers of cultural pathways adverse to an older order and generation.

More persons arrived into town from all over the world, to work with the AADP, and the around the clock. Various traffic intruded and came at odd hours that used to belong to the rampaging dominion of Egwu Abdu. It was beginning to shape up as a new world. Other than the AADP, new lifestyles of late or all night clubbing and dancing also evolved. Egwu Abdu’s nightlife and space-time now had new daring competitors. Beginning in the mid-1980s until the early 1990s Labmina hotels, with its vibrant clubs and dazzling dancing floors and roving strobe lights, predominated consciousness and created a new activities regime. Labmina quickly gained fame as the new gathering and bustling hub, competing with the buzzing motor park garage, with increased traffic and human influx.

Egwu Abdu, though culturally alien to Anyigba society, for as long as the masquerade form was deeply steeped within the traditional cultural imagination-linking masquerades to security and social vigilance, all was good. Egwu Abdu functioned quite well in maintaining law and order. But as soon as the forceful and transformative projects of modernity began to rear its swinging head, and stirring the hornet nests, society steered in another direction. Egwu Abdu could not win in the face of such alien phenomenon, and its massive onslaughts of cultural transformation. Egwu Abdu struggled and eventually it receded and retreated, honorably discharging itself into an underground current and rhythm.

Eventually, Egwu Abdu disappeared entirely from the Anyigba landscape and social memory; quietly taking its bow and totally exited. Exiting humbly, but even with a vengeance. It went with its spellbound charisma and even the memories of its existence. Egwu-Abdu did not even leave behind any traces, not even its ghost within much of the Anyigba temporal trail. Self-purgation, maybe! Its memory equally quickly faded, becoming something of the deep past, drowned, even if the timeframe and the time-capsule between its existence and exit was still shallow buried.

More persons poured into town from all over the world, to work with the AADP, and the around the clock. Various traffic intruded and came at odd hours that used to belong to the rampaging dominion of Egwu Abdu. It was beginning to shape up as a new world. Other than the AADP, new lifestyles of late or all night clubbing and dancing also evolved. Egwu Abdu’s nightlife and space-time now had new daring competitors. Beginning in the mid-1980s until the early 1990s Labmina hotels, with its vibrant clubs and dazzling dancing floors and roving strobe lights, predominated consciousness and created a new activities regime. Labmina quickly gained fame as the new gathering and bustling hub, competing with the buzzing motor park garage, with increased traffic and human influx.

Egwu Abdu, though culturally alien to Ayangba society, for as long as Ayangba imagination harbored the masquerade as not alien, but an integral feature of their society and still deeply possessing a transforming yet traditional cultural imagination, Egwu Abdu was at home and fine. The transforming society needed to be assured that features of its past existed, thus linking masquerades to security checks and social vigilance, was all good, especially as new trends evolved and new ways trending. Endorsed by the Ayangba community, Egwu Abdu functioned quite well in performing its law and order maintenance function.

But as soon as the forceful and transformative projects of modernity began to rear its swinging head, and stirring the hornet nests, society steered in another direction and Egwu Abdu, probably knew the game was up. Its dominance was ebbing. Egwu Abdu presumably knew what the auguries entailed. It could not win against these new forces. In the face of such evolving alien phenomena, and their massive onslaughts eclipsing the ease of Ayangba and its hitherto traditional contexts, with the emergent forms of cultural transformation, Egwu Abdu struggled a little, eventually retreating it honorably discharged itself into an underground current and rhythm that swept it away.

Eventually, Egwu Abdu disappeared entirely from the Ayangba landscape and social memory; quietly taking its bow and totally exited. Exiting humbly, but even with a vengeance. It went with its spellbound charisma and even the memories of its existence. Egwu-Abdu did not even leave behind any traces, not even its ghost within much of the Anyigba temporal trail. Self-purgation, maybe! Its memory equally quickly faded, becoming something of the deep past, drowned, even if the timeframe and the time-capsule between its existence and exit was still shallow buried.

Now, even many in contemporary Anyigba would remember the name and times of Egwu Abdu, when it held sway. Those who do struggle to remember, juggling to resurrect even superficially the memory and phenomenon of Egwu Abdu do so with vexed difficulty. The times have changed, modernity had knuckled Egwu Abdu into almost total oblivions. Egwu-Abdu once again became alien, racing past memory leaving no traces.

Increasingly, it is also equally getting harder to easily obtain cogent information regarding this masquerade phenomenon. Much of the facts and process regarding the Egwu Abdu was even then deeply held in secrecy, in the first place. Other than this too, many persons of that era are now mostly dead. It is even amazing that within a span of less than three generations that even within contemporary Anyigba much memories about the Egwu Abdu has been effaced and fast fading. Many of the younger ones have not even any vague inkling about this spectacular masquerade form that previously dominated in the popular imagination and affected the consciousness and ways of acting of many of the area’s then residents.

While, the fact of the easy loss of such cultural memory within a short duree of a population is interesting, it is equally troubling.

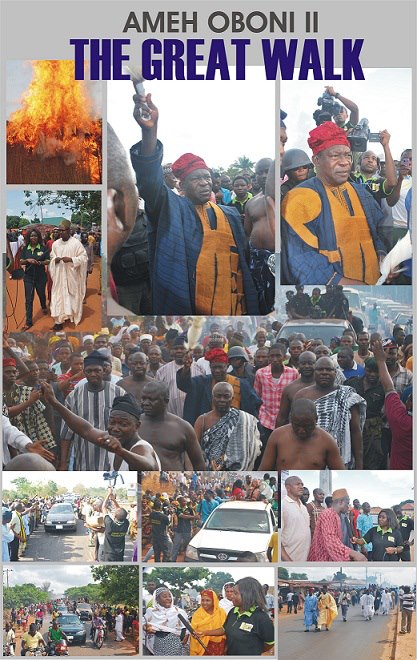

The issue of Egwu Abdu shows us about our Igala cultural acceptance and shaping of alien forces into serving our cultural and existential needs. This has always been the case in our history. Igala history shows an integrated fabric of different ethnicities that at varying times have contributed to the richness of our society at every point. Igala links to varying ethnic groups such as Jukun, Yoruba, Benin, Igbo, Hausas, Nupe, Idoma, Edo groups, in precolonial times, and our plural acceptance even in modernity of others bears testimony to our integrative abilities to resourcefully live in peace and acquire new forms of knowledge and materials that assists our wellbeing and progress. In fact, it must be noted that in 1841, our royal father, Attah Ameh Ocheje, who signed the treaty with the British on September 6th, 1841 had expressed openness to send his two sons to be trained in Britain by the imperial government.

We must always be open even in modernity to acquire and collaborate with others to effect the broader and overwhelming transformation of our social polity, and also economic and technological institutions, structures, and systems.

But, one troubling thing that the Egwu-Abdu unravels, is that we, Igala do possess a very short and even rudimentary attention span and memory of our historical conditions and social situations. There is no society that exists without the memories of her past and civilizations. It is often, sad, when many Igala are so intellectually shallow relative to their historical imaginations, yet many attempt to pontificate over histories they hardly know, embellishing and distorting authentic historical perspectives.

More cogently, if a significant event that predominated consciousness in a bustling Anyigba community in the modern era, can so easily be forgotten, what is our hope that the many efforts of our own generation will not equally be lost? What do we do? How do we go about it to retain our rich and evolving histories? Sadly, today certain abnormal or anomalous trends are surfacing that can either diminish or alter the Igala historical dynamics, and may also cause historical amnesia or social memory erasures.

In the next set of column, I would be talking about certain Igala persons, who simply but courageously left legacies of efforts in Igalaland. I intend to highlight the simple yet fruitful evolution of the efforts of the late Chief Demo Ogah, the Okakwu of Iyano, and the late Coach Patrick Achimugu, whose astute efforts in the arena of sports, specifically handball development in Idah and Kogi State, quietly but through certain serious backstage efforts, produced pride and spectacular results in their eventual outcomes.

To remember, and not to forget is to honor times, places, events, and people that made life worthwhile, and those things that life endorsed as worthwhile. It is also to realize that small and simple schemes can blossom in ways that become grandiose and whose effects are beyond reckoning. To remember is to live, to be remembered is to be alive!